ESSAYS & REVIEWS

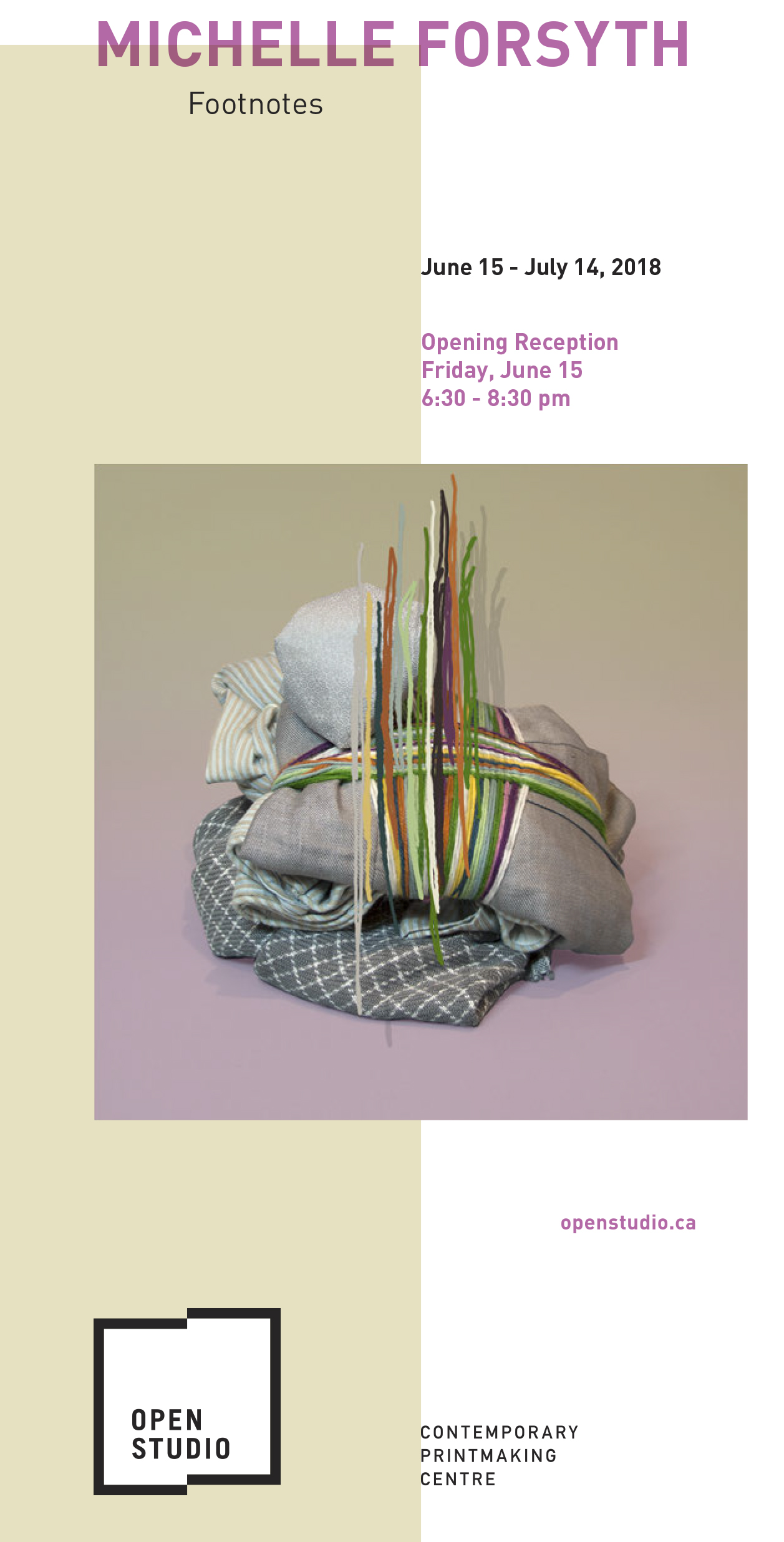

MICHELLE FORSYTH: FOOTNOTES

Exhibition Brochure

Open Studio

FOOTNOTES - MICHELLE FORSYTH

Text by Jenn Law

[+ Read ]

'Like' and 'like' and 'like' – but what is the thing that lies beneath the semblance of the thing?[1]

--Virginia Woolf, The Waves

When artist Michelle Forsyth was six years old, she had to sell most of her belongings when her parents decided to move to a sailboat. She had a bunk, one shelf for her remaining possessions, and a single drawer for her clothes. Their family lived on the boat for six years, moored in a British Columbia marina during the school year, and setting sail on various adventures in the summer months. It was a formative experience that has shaped the artist’s relationship to material things and her concept of home. If objects create a sense of being at home in the world, reflecting us back to ourselves, then, as Martin Heidegger tells it, the experience of being unhoused inevitably evokes angst in the individual.[2] In this, “what remains is a subject whose objects have abandoned it.”[3] To the artist, however, such angst is productive, even necessary – allowing her to see the world as it truly is, in order to open up new possibilities.

Home is the starting point for Footnotes, both literally and conceptually. Forsyth’s current abode, a compact basement apartment in Toronto, functions as a fluid live/work space. To visit is to enter a domestic archive, everything methodically curated and displayed. Forsyth’s space is full without feeling claustrophobic, as she takes great care to ensure that everything may be seamlessly tucked away. Things are routinely arranged and rearranged, wrapped and unwrapped, and occasionally given away. In the artist’s collection, every object is relevant. Home, for Forsyth, is not a fixed place in time and space; it is a process in the constant throes of reinvention.

The impulse to make work from her surroundings was fortified when Forsyth was first diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 2009. That year, she decided to focus on what was going on immediately around her, rather than responding to external social issues.[4] Ultimately, however, the artist’s work moves beyond a mere concern with the domestic sphere, probing deeper ontological questions concerning what it is to exist in the world. Forsyth’s first body of work from this period consisted of paintings of her then-husband’s plaid shirts. Mimetic exercises in abstraction and repetition, these works are studies in intimacy and loss, each shirt copied and distilled to its essential formal elements, marking a desire to create meaning through pattern in an indexical way. Forsyth employs wide-ranging strategies of copying in her practice. Over time, her work has evolved into sumptuous, trompe l’oeil creations, layering multiple objects and processes into carefully staged compositions.

In Footnotes, each piece begins as a sculptural assemblage composed of individually hand-crafted copies created through diverse means, including hand-woven textiles, lithographs, silkscreens, paintings, papier maché, and textual anecdotes. Through the variable copy, the artist reiterates the object’s originality over and over. Its singularity is amplified in being reproduced, not diminished or subsumed. Each copy represents a close reading of the object, a focused exercise in understanding. Learning new mimetic processes has become, for Forsyth, a means of accessing the object from varied perspectives and coming to know it through multiple points of re-inception.

Though the final versions are presented as photographs, photography is merely the concluding act in an elaborate production. Forsyth edits the final layered image, adding in false backgrounds or shadows and screenprinting on top of the photograph in order to play with dimensionality and manipulate the viewer’s perception of proximity/distance. Consciously employed as both a conceptual and technical method of flattening the image plane, photography is a mediating tool, allowing the artist to push the opticality of the image while simultaneously creating a further layer of separation between the viewer and the work.

This photographic veil likewise obscures the evidence of the artist’s hand embedded within the image. Yet, the body and its labour remain central to these pieces. Several of the cloth bundles are dresses hand-made by the artist, many of which she can no longer wear as Parkinson’s takes its toll on her body. Other bundles are made from clothing gifted to the artist by friends. Often the only clues to their original corporeal functions are found in anecdotal texts accompanying the work. In more recent pieces, Forsyth references the body more overtly. In Old Jokes (2017), for example, a hole is cut into a painting through which a hand-sewn plaid glove reaches out, filled with the artist’s hand grasping a crumpled plaid paper bundle.

Many of the bundles contain hidden messages tucked deep within their cores like secrets. Forsyth similarly wraps and unwraps personal items in her home – childhood photographs, books, and other items of personal value. There are some things so precious, so vibrant to behold, that we must turn away our gaze. It is a quality, of course, not inherent to the things themselves, but the access those things grant us to some part of ourselves and our history that may otherwise remain inaccessible. The object here simultaneously functions as corporeal weapon and wound, recalling Joseph Beuys’ 1979 sculpture of a knife bound in gauze, When you cut your finger, bandage the knife.

In the language of still life, the body itself becomes a thing among things. For Forsyth, this work in part bears witness to the struggles of the body; the labour invested in its meticulous making, a triumph over the disease.[5] As Elaine Scarry writes, “what is quite literally at stake in the body in pain, is the making and unmaking of the world.”[6] While Parkinson’s does not define Forsyth’s work, it informs her practice in intimate ways that remain largely invisible to the viewer.

“’Like’ and ‘like’ and ‘like’,”[7] writes Virginia Woolf, but can we ever dig deep enough beneath the simulacra of the thing to reach its essence? The thing can never speak to the full profundity and mystery of human experience, to its joys and its suffering. Yet it can serve as a footnote to a life unfolding, filling out and embellishing its hidden depths in ornate, spectacular detail. In the end, perhaps, semblance is enough, for it is here, in the material enchantment of likeness and affinity, that sympathy is revealed. Home, after all, is repetition.

[1] Woolf, Virginia. The Waves. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015, 95.

[2] Refer to Schwenger, Peter. The Tears of Things: Melancholy and Physical Objects. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2006, 69-70.

[3] Schwenger, The Tears of Things, 69.

[4] Forsyth, Michelle. Interview with Jenn Law, February 21st, 2018.

[5] Forsyth, Interview with Jenn Law.

[6] Scarry, Elaine. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985, 23.

[7] Woolf, The Waves, 95.

INTERVIEW

Conducted by Irina Tomshinsky, a 4th year Criticism and Curatorial Practice student at OCAD University. The following interview was for a class titled: Proseminar: Curators & Critic taught by Paulette Phillips.

[+ Read ]

IT: Could you briefly talk about your university experience and what was your practice like, back then? What were your interests? Did you have a preferred medium to work with?

MF: I went to the University of Victoria and studied photography and sculpture, even though I made paintings. I went to Graduate School at Rutgers. When I was a grad student I was a figurative painter at that time, so I went to study with Hanneline Rogeberg and Joan Semmel. Overall, my education experience was excellent. I wouldn’t have changed it. My undergrad program was very conceptual, so we didn’t do any traditional drawing. And my grad degree is in interdisciplinary media.

IT: Now that you are a professor yourself, do you feel that the student experience changed and how is it different from back then?

MF: Well, obviously the Internet is around. When I was an undergrad there was no Internet or, it was just starting up. I didn’t have an email either at that time. I think I got my first email in 1997, and I graduated in 1996. So when I was a student I was typing up papers on a Smith-Corona word processor, and I would have to adjust every line, so it was quite different. We didn’t have a computer lab in the Fine Arts building, we had to go and use the computers in Art History. So there were no digital manipulation of images or anything like that.

IT: Do you think that this is why your practice is so hands on?

MF: Not because of that. But it’s hands on because I grew up in a family where my mother made everything. She made all our toys and clothes; even our board games were made from cardboard. So, I grew up making everything.

IT: When you start new projects, what is your process like? How do you get inspired and get your ideas?

MF: It’s interesting that you say, “start new projects” because I don’t think of myself as starting new projects but just always continuing the past ones and they morph and change into the new thing. I have new ideas…

IT: How do you come up with those?

MF: I have so many ideas I couldn’t make enough work to explore them all.

IT: Do you have any particular sources of inspiration that you draw from?

MF: Nest Magazine, Interior design, color, fashion, the home. I don’t really read art magazines, but I read design magazines. And Pinterest, I use Pinterest a lot. It’s my digital sketchbook.

IT: As I was browsing through your website, I noticed a common trace in your works, all of them in one way or another have a grid. Is that something you can comment on?

MF: When I was an undergrad, I did everything on the grid and my professor Mowry Baden always told me to get away from the grid. And Jessica Stockholder who studied with Mowry Baden early on said: “don’t listen to things that your professors say take your own path.” So I use the grid a lot. I feel like the grid is this point where the Matrix of craft meets the matrix of digital and it’s also a way that we use in painting to transfer images. And weaving too, weaving is based on the grid.

IT: I also noticed that all your projects are very meticulous in their execution and almost obsessive in their fabrication. It can be seen right away that a large amount of work is invested in them. Nowadays, in university, instructors often tell us to find ways to simplify the process and find faster and more convenient ways to execute the work. In your practice it appears to me that you do just the opposite, can you comment on that?

MF: It is an interesting thing that you say that. Because when I was a student, professors said the same thing to me and I always did the opposite of what I was told. Because it was more interesting than simplifying the process, simplifying the idea, and my ideas are pretty complex. I don’t want to create a one liner with my work, we don’t think that way and we don’t communicate that way and our minds switches gears all the time, so I like to put all of that into the work.

IT: Don’t you occasionally find it frustrating when you have such a large amount of work to execute?

MF: No, I don’t. I have works that I’ve been making for years and years. It doesn’t bother me because I have so many projects on the go. I have more than thirty things going on at a time. And so, people say it looks like I’m really productive but I just have been working on all of it for so long that when projects finally get finished it looks like I have done a lot.

IT: Do you set timelines for yourself?

MF: I set goals. And they are more general and vague and not related to one piece or another because I don’t like to rush my work. I find the working on the work, the most important part. In fact when it leaves the studio I feel a bit sad because it somehow looses something when it’s divorced from the context of the place where it was made.

IT: Do you think that is why you work in series?

MF: I just get an idea and explore it for a while. I want to think about all my series as being one body of work. There is a book titled The Plague by Albert Camus and in it is a character named Grand who is working on his masterpiece, which is a single sentence, repeated in different ways. And I think of that in a similar way to how I work. If the painting didn’t work, I will try again and try again. I feel that in a sense all my works are the same work I’m just trying t get there and I never do.

IT: Do you think you will eventually get there or is all about the process?

MF: Well, I hope so at the end of my life. If I got there then there wouldn’t be anything to work for.

IT: Another thing I noticed is that you love plaid? Is there a reason?

MF: When I was married, my husband went on sabbatical and that’s when I started painting plaids. I started painting the reproductions of all his shirts that he left in his closet. It actually started out when I was thinking about this book titled

Microserfs by Douglas Coupland. In it there is a group of people who are writing code on a video program based on Lego. One character locks the door and works really hard on the code; he stays in there for a few days. His friends were getting nervous that he wasn’t eating so they bought him flat food and pushed the food underneath the crack in the door. So, I though instead of going out into the world doing work about other places, what happens when you are closer to home and close the door. I also wanted to work in the studio as if I needed flat food because if I worked hard enough to need flat food then I was really onto something.

IT: Are you at all interested in creating displays for your work? You have works that are displayed on the wall using needles and some that have pedestals and also sculptural works that are inspired by those pedestals.

MF: I am interested in display but more than that I am interested in rupturing our expectations of what we want to see, is it a photograph or is it a painting would be the question that comes up most often in my work. But also, what is ok to make right now and what is not ok, what if we tried out some of the modalities of work that are not in fashion. And thinking about displaying all of those works together that have all those counterpoints that meet but also try to mess with it a little bit.

IT: When you say what is ok to make and what is not ok to make can you elaborate on that?

MF: I’ve read this article recently called “like art” about Instagram. You get all the likes but how much work is being made to be or, somehow comes across on that media online, that is likable and what is not likable it is something I think about. Figurative painting and autobiographical work is not necessarily in vogue right now. So I’m interested in exploring that space.

IT: Speaking of autobiographical work, as far as I know, you are working on a memoir right now. Can you talk about that?

MF: Well the memoir started because--if you noticed all the works have text that goes with them--so the text and the image were always at odds with one another. With painting you don’t necessarily anticipate to have a text block to go with it, where with photography you do see that often. Because people wouldn’t know that there was text so I thought maybe I’ll get rid of the images because, I’m good at images and play with that text for a while to see where it goes without the image. But then I started bringing images back into the text again.

IT: I did notice that there are small illustrations that accompany the text. How would those be incorporated?

MF: I have a book that I had as a kid in the 80’s, it is a home decorating book and I’m laying out the whole memoir in that style. So the home decorating book becomes a place where the line drawings that mimic the line drawings of the history of furniture that are in the original book. And the book comes up in the narrative about my life that’s the place where I start. I met Richard Hunt who teaches graphic design and showed him some early designs and he suggested I respond to something I know so that was influenced by him.

IT: You have work that deals with trauma in particular, where you photograph the site of catastrophes and the photos not necessarily portray the wreckage of the disaster but other subjects in the area. How do you pick those images you choose to work with?

MF: For those I actually travelled to the site and documented hundreds of photographs from the site. When I got back to the studio I picked the ones that I thought were the most poetic. I use intuition in the studio a lot. I consider it a version of play. And I feel if we don’t allow ourselves to play then what are we doing? Because play for me is very important in my work. I used to make work that was very serious and then, I had to do these goals for my job. Every year we had to submit our goals. And all my goals were goals about advancing etc. And when I got diagnosed with Parkinson’s I wrote my goal and it was only one sentence. My goal was not to have any goals. I realised that nobody read it because the response was the same as the year before and that’s when I decided I will go into the studio shut the door and make what I want t make. And if I change my mind and want to make something else on the next day, I wont feel bad about it. I’ve since started writing goals again though.

IT: How do you deal with storage?

MF: I don’t believe in having a storage outside of my place and I think its because I grew up on a boat and we came up with ingenious ways to store everything. I have everything stored in the cupboards in my studio, bedroom I have things in cardboard boxes and bins. I’m really organized. I made a pedestal system that I’m still working on where you can put it together and take it apart like Lego to circumvent the storage problem.

IT: You mentioned that you grew up on a boat is that where your need for organization comes from. And is that why you are drawn to grids to figure out where to place things?

MF: Yes, I wrote my graduate thesis about that.

IT: You work in a lot of mediums; do you have a preferred medium that you are more comfortable with?

MF: I think, I’m most comfortable with painting. I often distrust painting. It’s a love/hate relationship. I think that painting is a lie by its nature. You are putting colour pigment on the surface to create fiction all the time. They are constructions. But painting also records the mark of your body, which I am excited about. I’m actually getting more excited about performance. Not performance in the typical way that you would think. But in the sense that every time you make a piece of art you are performing. I am trying to find a place to unveil that in my work is something I’m interested in looking into.

IT: Are you interested in displaying the process of making the artwork as an artwork?

MF: An artwork that built from process displays that naturally. I think because I have difficulty doing simple tasks like getting dressed., doing up zippers knitting, and doing things I used to do really fluidly. The process of making work becomes now more important because it is more of a physical feat to do the stuff that I used to do.

IT: Does that make you readjust the way you work or do you continue to use the same process but have to put more effort into it?

MF: Yes, the second one. I think about the turtle that won the race just keep gong slow and you’ll get results. You just have to put in more time.

IT: With your work being so meticulous and time consuming aren’t you tempted sometimes to find an easier way?

M.F: When I was an undergrad, I made paintings really fast. I made a painting in a day. And then I realized that as an undergrad you don’t have that opportunity to spend a year on a painting because, if you spent a year on a panting and it failed you’d fail your painting class. So when I finished my undergrad, one of my strongest desires was to make a painting that took along time to make. And then I started doing that, spending time on work. I thought it was a lot of time, at the time, but now I feel that I still made fast paintings.

IT: In some of your works you use certain patterns to paint, is that something you do digitally?

MF: No it’s analog. I used screen-print overtop watercolours but before that I was using transfer paper to transfer those lines. In a sense it was a way to make handmade pixels. It came out of the fact that I hated washing brushes and I worked with oil paints and so I thought if I just use small brushes then I don’t have to wash them very well. Then I started to use those tiny brushes to make my paintings and build them out of lots of marks. I started organising the marks more like a digital skin. Because all those images earlier came from the web I wanted to slow them down. In graduate school I was making those huge paintings. Then when I finished I didn’t have a studio and thought I’m going to make those little petty points where every pixel is hand stitched.

IT: Those are very beautiful.

MF: But it’s horrific too, since this is a car accident victim and his face is all torn off. So I was taking those horrific images from the web and stitching them up to appear beautiful.

IT: Why were you drawn to such imagery?

MF: I wanted to take these images that we see everyday. They are so ubiquitous, we see them really fast and I wanted to slow them way down. To take fast images and make them slow through process. And this is where I was thinking about this grid as the matrix of craft meets digital. But I also like to use technology to slow my process down rather than speed it up. For example: all of the drawings in my book are made with illustrator and not by hand.

IT: I would assume you aren’t using a tablet.

MF: No, I use the track pad on my laptop.

IT: I’m trying to understand the reason as to why you are trying to slow things down so much?

MF: To give me time to think. When you sit there and knot a sweater, that kind of slowness allows for so many things to go through your head.

IT: We had a talk in class where one of the guests said that, it is a generational thing where nowadays students have a shorter attention span and need things to be more dynamic.

MF: Do you think that’s true? I don’t like those generalizations between generations. Because, how do I know what your experience is like? And how do you know what mine is like?

IT: I guess a lot of people will have a difficulty grasping why you are trying to slow your process down when so many are trying to accelerate theirs.

MF: Well, why are we making things so quickly?

IT: I guess, some people try to make more room for other projects but as you said, you work on yours simultaneously. And others are producing works to meet deadlines.

MF: I don’t have that pressure because I have a teaching job. And I don’t have a dealer right now. I had a dealer before in New York and I was always making work for art fairs. You have deadlines where you need to have a certain amount of works for this or that art fair. But I really enjoy the fact that I can make works at my own pace. Because when I was younger I always had an interest in getting into this show or that show but now I’m interested in putting my work out in the Toronto art scene. Because a lot of people don’t know my work but its more of a conversation rather than checking shows off my list. Because I had a lot of shows and I don’t need to have more shows unless it’s interesting to me.

IT: So it’s quality over quantity?

MF: It’s more like if I can discover something by showing it then I’m interested. I have a show coming up in June with Colette Laliberté at a little storefront space that a friend of mine has and I’m exploring my props that I use in my works. I’m making little individual shelves for them. And the shelves have painted shadows on them that are painted just like the objects. I’m getting really interested in these shelves as a site for painting. I’m trying to make the work do something as interesting as it does in my home. Because, when it’s in my home and I take it out and I set it somewhere it has a relationship to the things around it. For example, the little watercolour on the wall is a watercolour of the larger painting next to it. And its more interesting seeing it on the wall besides that big painting than it would be separate from it. I am trying to figure out how you can get that kind of conversation to happen in a galley and I think that it’s impossible. That’s why I like showing in stores or other spaces that aren’t necessarily galleries. And that’s where I’d like to show more of my work.

IT: So you are trying to move away from the white cube to maintain the “hominess” and relationship?

M.F: I’ve been working in this home for four years now and I like what is happening with the work when it is in the home. And I don’t think that I’m trying to maintain that yet, but I just enjoy the work in the home more than outside of it. The work is different in the gallery, it becomes isolated like jewel. I call it “a jewel on a wall” where as the same piece is at home it’s like a “needle in a haystack”. And I like the needle in a haystack more than the jewel on the wall.

IT: is that because it allows you to look for the works and discover them as opposed being presented with the work?

MF: I don’t know because that is the perspective of the viewer who encounters this. But I live with those works all the time. Every pattern in my work comes from an article of my clothing. There are multiple conversations happening in the home between the objects and my stuff. And where does your stuff end and work start? I’m interested in blurring that line. When you have a stacked two items sitting on a shelf or on your table, is that as viable as when you stack two items and take a photograph of it? Those are the kind of questions I like to ask myself.

IT: There are a lot of floral motifs in your works is there a reason for that?

MF: This is a bit of an older concern but the flower motifs that are in my work now are because they are in my clothing. Before I used a lot of flowers because I was making pieces that I saw as memorials. And flowers are often left on memorial sites. When I started the one hundred drawings project. The first site that I documented had plastic flowers on a grave. So that kind of impulse to beautify something that’s horrific I think that that’s where it started. But now the flowers in the work I choose floral clothing its more of a reference to my earlier work.

IT: What inspired you to become an artist? Did you always want to be a part of this world?

MF: I always wanted to be creative. My sister and I grew up on a boat we had no toys we just had boxes we kept at the end of our bed that we called our “busy boxes” and they just had pencil and paper in them. And colouring books and we would just draw for fun together. When other kids might have played with Lego or computer games we just had drawing contests. Now my sister is a painter too, we both came from that creative place.

IT: Is there any relationship between your and your sister’s work?

MF: there are times when we share ideas, but not intentionally. We don’t talk that often because she lives in Edmonton but when we do chat together we realize that we have often been interested in simmilar things.

IT: So to wrap things up, can you talk about any upcoming shows any future plans?

We did talk about your memoir so what else is happening?

MF: I have a show with Colette Laliberté in June; I will have a piece in the vitrines at The Harbor Front and that’ll open on June 24th. I have a solo show in the main space at Open Studio in January. And then I am working on a show in Hawaii for next spring. And I am still looking for funding for my book because it is an expensive project.

HANDMADE ABSTRACT

Exhibition Catalog

Artists include: Katie Bell , Maria Chavez, Michelle Forsyth, Carl E. Hazlewood, LoVid, Marisa Manso , Lael Marshal, Christian Maychack, Leeza Meksin, Liz Nielsen, Courtney Puckett, Mary Schwab, and Lizzie Scott

HANDMADE ABSTRACT

Text by Elizabeth Ferrer

[+ Read ]

There is no abstract art. You always have to begin with something. - Pablo Picasso

Handmade Abstract presents the work of 13 artists who give new relevance to abstract modes of creation. Pursuing a range of formats including sculpture, video, photography, installation, mixed-media constructions, and sound, these artists employ materials and fabrica-tion techniques that contextualize their work in relation to everyday, physical realities. Tellingly, only a single artist in this exhibition pursues painting on canvas, although many other artists represented here demonstrate a deep consciousness of painting and its modern history. Earlier generations of artists, beginning in the first decades of the twentieth century, saw abstraction as a pursuit set apart from (or transcending) representational art and quotidian subject matter. And working with this mode, they articulated varied intents, whether in their work or by way of impassioned manifestos: To eliminate per-spective and spatial depth, meaning that the artwork was no longer a “window” to another world, but a thing in and of itself. To evoke the spiritual or the universal. To spontaneously express pure emotion. To pare down visual elements to a core essence. The artists taking part in Handmade Abstract bring forth a new goal, to affirm abstraction as an inescapable presence in the world around us, and these artists’ works are meant to reflect or interpret a world close at hand. Abstraction is everywhere, whether at home, in clothing patterns, in our technology, shipping boxes, construction material, even in the sounds around us. The personal and the mundane become filters, departure points for art works made with a sense of openness and improvisational free-dom, unconventional materials and processes, and a fine disregard for old hierarchies and boundaries between disciplines.

Many of the artists in Handmade Abstract work with found, often cast-off or recycled materials, eschewing traditional artistic media. Common materials and quirky process provide rich layers of evoca-tions — with the history of materials and their associations with our personal histories, with construction and craft techniques that speak to manual labor and domestic craft, and indeed, with the history of abstract art itself. For her wall-based works, Lael Marshall stretches dishtowels, handkerchiefs, and other fabrics over handmade, irregu-larly shaped stretchers. These intimately scaled works clearly refer to domesticity (a theme referenced by several artists in the exhibition), but also, to a kind of eccentric minimalism that reveals the essential qualities of her materials — their color and pattern, tautness or elas-ticity, and translucency. Marisa Manso’s installations include office cubicles, lighting fixtures, and electrical wiring, materials that play dual roles in her works. The lighting fixtures (often found in garages or offices), act as both illumination and as formal elements; wires play a functional role while also offering a linear element, extending the work over the expanse of a wall. And the cubicles act as either visual support or as demarcation of a space, one that recalls white-collar labor, a decidedly different relationship to the handmade. Katie Bell constructs wall-based works out of construction detritus, transform-ing the color, texture, and shape of these elements into energetic

compositions that simultaneously inhabit and create space. Sculptor Mary Schwab bases her work on used, cardboard shipping boxes. She gives dimensional shape to the void, the empty space inside the boxes, by casting with Hydrocal, a substance that also registers the irregular surfaces and textures of bubble wrap or other wrapping materials left inside the boxes. Schwab sees these as hybrid forms, both sculptures and surfaces for painting. And once she paints these forms, they attain a bright hue and viscous sheen as well as a person-ality — they are abstract and yet strangely familiar.

Although none of the artists here pursue perhaps the most typical form of abstraction, pure painting on canvas, many speak of their work as an alternative to painting; the expanse of wall or the space their works inhabit as ground, and their materials as source of line, gesture, color, and texture. Carl E. Hazlewood works with a range of materials including colored paper, cord, tape, felt, and other fabrics, materials transformed into formal elements in assemblages that he constructs directly onto the wall. Originally a painter, Hazlewood’s compositions maintain a fluid elegance and rich sense of materiality. His constructions are ephemeral, created in situ, as site-specific works that he ultimately destroys. Hazlewood photographs them while they are on view, using details of the compositions as starting points for smaller-scale mixed-media prints.

Courtney Puckett, who also began her career as a painter, creates sculptural works by wrapping yarn, thread, and other materials around pieces of cast-off furniture and other improvised armatures. She fashions freestanding and wall-based works that loosely suggest useful objects and that resonate with the spirit of craft, especially fiber art techniques. Puckett aligns herself, as she has stated, “with women artists, particularly those in the 60s and 70s who challenged the (pre-dominantly-masculine) rules of painting. What began as an intuitive gravitational pull toward soft materials has become an intentional reframing of techniques associated with ‘women’s work’ in order to disrupt hierarchical and categorical divisions within art.”

With disparate media, Michelle Forsyth, Leeza Meksin, and Lizzie Scott create work that references the human form, even while remaining essentially non-representational. Forsyth, a photographer, stages scenes using painted pedestals, clothing (often her husband’s shirts, chosen for their color and plaid patterns), and paper back-drops. She photographs arrangements of these objects in a way that confuses what is a real object or materials and what is imitation. For-syth’s play of pattern and color become a play on geometric abstrac-tion, while remaining grounded in the everyday, or what she calls, “the poetics of lived experience.” Meksin creates site-specific installations in built environments, constructed with spandex, zip ties, and various kinds of weights that possess both structural and aesthetic roles. Her installations connote the scope of architecture while also referring to the body and to processes of covering, dressing, stretching, and decorating. Meksin notes that she works at the intersection between abstraction and representation, her works embodying a tension between body and built space, abstraction and functional form. Scott makes hybrid “object paintings” with muslin, other textiles, and bubble wrap. Shaped like sleeping bags, her Drifters are both abstract paintings and quasi-functional objects that can be displayed folded, hung, or leaning against a support. These works evoke both comfort and a sense of strange “otherness,” as she says. They relate to the shape of the body but as Scott notes, these “sculptures are like alien bodies — hybrid, lumpish, other.”

Particularly in the mid-20th century during the heyday of Abstract Expressionism, artists endowed great symbolic value to the materiality of the painting; paint as expressive substance, canvas as evocative ground, and the painting itself as object. Larger canvases during this era became a physical space, an arena in which the artist could act rather than merely portray. Even brushstrokes became fraught with meaning. While this exhibition focuses on work that moves emphat-ically beyond painting, these artists similarly focus on the expressive value of materials and on means of fabrication. The artist’s hand is of-ten overtly visible, for example, in Leeza Meksin’s mode of stretching and weighting or Courtney Puckett’s wrapping and connecting.

In addition, many of these artists have devised idiosyncratic modes of producing their work. Christian Maychack molds pigmented clay epoxy into handmade wooden armatures and then sands, polishes, carves, or scrapes the clay to achieve varied surface textures. His objects simultaneously reveal positive and negative space, front and reverse, evidence of fabrication against highly finished surface. This “state of indeterminacy and paradox,” as Maychack calls it, becomes a defining quality of works that challenge old artistic hierarchies and that seem to inhabit the restless in-between space of painting and sculpture, physical object and abstract image.

Liz Nielsen’s photograms are produced from handmade negatives that she makes from transparent colored gels cut into abstract shapes and then arranges onto Plexiglas. She exposes these negatives onto light-sensitive paper and when printing them (in a darkroom through an analog, not digital process), produces a negative image. Green forms become red, yellow becomes blue, white becomes black, and layered forms generate colors that are the result of Nielsen’s years of experimentation. These images often contain reminders of the real world — a horizon line suggests a landscape; specific colors or forms call to mind plants or features of geography. Nevertheless, her compositions are adamantly abstract, based in the foundational building blocks of non-objective art, form and color, and reflecting a world unto themselves.

Handmade Abstract also includes video-based work by the interdis-ciplinary collaborative LoVid, and a light and sound installation by Maria Chavez. These artists are the subject of two interviews by exhibition co-curator Jenny Gerow, published in this catalogue. Their inclusion in this exhibition is meant to provide an expansive definition of abstraction — it is not limited to physical objects, but can also be experienced on screens, in space, and aurally.

The artists represented in Handmade Abstract invigorate the dis-course on abstract visual language by creating revelatory forms out of materials and processes that are grounded in palpable, lived reality. It is the artist’s hand, as well as their modes of fabrication, that result in a kind of alchemy — they simultaneously reveal and transform their materials, producing a transcendent experience of the commonplace.

ENTR’ACTE

Exhibition text by Caroline Langil and Andrea Fatona

[+ Read ]

Entr’acte 1 brings together work by artists, who are either faculty or recent alumni of OCAD University. The RBC Gallery, installed in the Ontario Heritage site of the Winter Garden Theatre, in the heart of the city, provides a unique opportunity to focus on the work of emerging artists. In this case the juxtaposition of work by recently-graduated students with that of faculty gives viewers the chance to see how OCAD University generates a vibrant, imaginative and dynamic environment where creativity thrives. The title of the exhibition is an entry point to this notion. The title, Entr’acte,has multiple meanings, and thus provides multiple entry points for the viewer to consider the work shown here. It can refer to a pause between the stages of a production, but it is more likely to be a piece of music played between the acts. Each of the works presented in this exhibition have their own sonic resonances, but together they create a contemporary symphony, or perhaps more accurately, an eclectic playlist of interdisciplinarity wherein art no longer marches to the beat of one drum.

At the outset viewers are greeted by Anda Kubis’s, Night (2014) which on first glance has all the attributes of a painting, but on closer inspection proves to be a digital output of vibrant, deep colour. Oscillating between what we know and traditionally understand to be a painting in terms of its positioning and behavior, Night sets the stage, so to speak, for an exhibition wherein our expectations of art are upended. Deep looking is required here in order to disentangle our perception and the reality of the media being utilized. The potential of illusion, so evident in Kubis’s surface, is similarly deployed as a tactic by Michelle Forsyth in her uncanny triple-threat objects that are equally paintings, textile works and sculptures. What appear to be discarded bundles of clothing are actually, on closer inspection, newly woven fabric entwined with painting and treasured items. The stories of these bundles are as significant as the works themselves and so are provided for the audience as extensive footnotes to the titles of the individual works, Checkered Bundle3(2014), and Yellow Bundle (2014). Again, colour is intense, acrid, jarring but also symphonic in the way Forsyth weaves it through both fabric and paint. The artist begs us to look carefully, and those who do are rewarded with an optical treat on the receiving end of the bundles, on top of the pedestal.

The weave of the fabric in these works is mirrored within the engraved surface of Rebecca Ladds’s proximal work “Relic Query?”(2014). Modest in its presentation, this diminutive work of a woman’s hands in her hair, bracketed by design tropes drawn from the Renaissance, harkens back to a period where the value of art was often determined by the virtuosity of the artist. But this is an object normally on the way to becoming an artwork. It is a plate, the matrix, etched in preparation for printing. So we are seeing something at mid-stage, between the acts of production and completion. Similarly, Lisa Myers’s Strawberry Spoons (2008), which reconsiders the beauty of the everyday, asks the audience to stop, pause and look at something on its way to conclusion. Myers picked strawberries, reduced them and then carefully dipped the spoons in order to create a dip line that functions as a means to “draw” her process of jam-making.

This minimalist rendering of the domestic lies in sharp contrast to Alex McLeod’s intensely detailed and extravagant landscapes included here. While Myers relies on the properties of her materials to tell her story, McLeod presents us with synthesized objects en masse that, nevertheless, feel remarkably familiar. Recalling childhood icons of dreamy landscapes; of cartoons, picture books and even hallmark cards, these works tap into our lives between one day and the next where dreams allow us to play out our deepest fantasies and fears. Franco Archieri’s Astral Noise (2012) similarly engages our collective imaginations, however as an object it is unnervingly real. Using a technique known as coiling, Astral Noise is woven from recycled cloth. Referencing the human form, it is suggestive of the performance it enables. Archieri performs this work as an ethereal sound sculpture, with eerie tones emanating from the textile carapace. Once again, as with McLeod’s nods to childhood, we have some reference points – yetis, monsters, Sasquatch – but somehow the fabric, with its nod to the feminine, throws this off and we are left questioning the normative nature of our fears. Finally, coming back to the potential of fabric to remake our perceptions of what constitutes contemporary art, Hazel Mayer’s cascading Ding Dongs (2013)playfully create a cacophony of colours, textures, and patterns that defy easy categorization.

The works in Entr’acte speak to, and revolve around ways of seeing, perceiving, and knowing. Each piece demands a practice of deep looking in order to disentangle the sense of what we are looking at. In Sources of the Self, philosopher Charles Taylor proposes that painting “…makes us see things with a freshness and immediacy which our ordinary, routine way of coping with the world occludes.” 2 This exhibition provides evidence for the way contemporary art renews Taylor’s 1989 observation of art’s effect through 21st century interdisciplinary tactics. Taking pause to attend to the works in this exhibition, and look deeply, is a lesson to be taken beyond this gallery, and to our everyday lives as we navigate a new century.

Andrea Fatona and Caroline Langill

1. Entr'acte is French for "between the acts" (German: Zwischenspiel, Italian: Intermezzo, Spanish: Intermedio). It can mean a pause between two parts of a stage production, synonymous to an intermission, but it more often indicates a piece of music (interlude) performed between acts of a theatrical production. In the case of stage musicals, the entr'acte serves as the overture of Act Two (and sometimes Acts Three and Four, as in the case of The Student Prince). In roadshow theatrical releases, films that were meant to be shown with an intermission, there was frequently a specially recorded entr'acte on the soundtrack between the first and second half of the film. http://www.translationdirectory.com/glossaries/glossary310.php

2. Charles Taylor, Sources of the Self: The Making of Modern Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. p. 468.

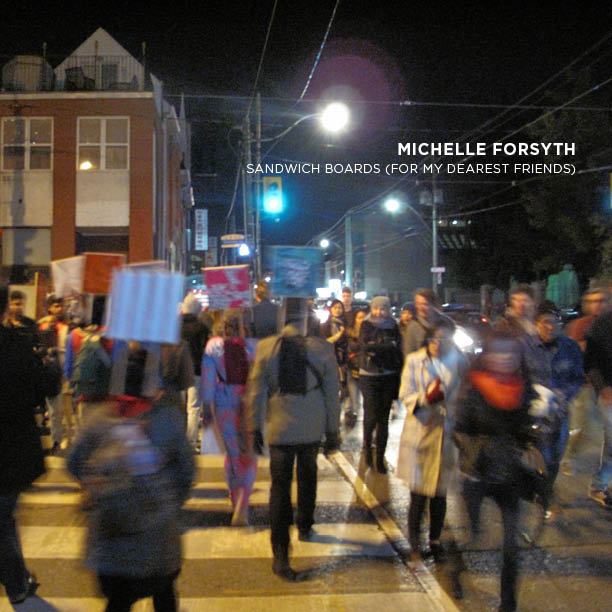

MICHELLE FORSYTH, SANDWICH BOARDS (FOR MY DEAREST FRIENDS)

Karl-Gilbert Murray, Historien de l'art

for Nuit Blanche Independent Project Catalogue

[ + Read ]

In a crucial effort to engage with the spectator, the work Sandwich Boards (For My Dearest Friends) is designed to shift our perception of the immovable nature of things. Primarily, the work consists of walkers/carriers making their way through the streets of Toronto in sandwich boards, thus freed from the constraints of established art institutions, peddling a collection of painted reproductions of textiles with decorative patterns that imitate the clothing worn by the artist’s close friends. Conceptually1, each board, by revealing a number of emotional relationships that transcend the symbolic iconography of the geometric, tiled and/or floral prints, signifies a friend — physically absent but very much present, embodied in the formal and stylistic forms of the print fabric.

Constantly morphing as it wends its way from one place to another, the work reveals a panoply of cultural atavisms that, depending on the context and the influence of the environment, elicit personal recollections through fortuitous encounters. A wearable work, it reminds us that not only does clothing play an important role in our daily experience of others, but also that fabric envelops the body and, like a second skin, conveys things differently. Nomadic, the work proceeds along a path initiated by the walkers/carriers who, through their random interactions, stage the body-mounted paintings, establishing a communication dynamic that goes well beyond a simple urban stroll.

Hence, one might say that the work defines a set of distinctive signs since these body-mounted paintings, informed as they are by references to Forsyth’s personal relationships, weave a gallery of portraits, especially the ornamental aspect of the prints, which influence our judgment (too often constructed by prejudices). Also, however, powerfully evocative and laced with elements liable to stir up forgotten moments, words, acts, and even the scents of life, the prints both attract and elicit memories. Indeed, invested in memory-evoking potential—as if to seek balance or a stylistic analogy visually linking the canvases to the individuals to which they refer—the work conditions our image of the other. An image invented according to our own subjectivity and creativity whose process of fabrication, complete with imperfections, reinforces the unique character of each painting. Thus, the work expands upon the uniqueness of decorative patterns that, rooted in the world of emotional memories, induces a sense of proximity between the public and the work.

So, in the name of democratization, the work hopes to embed art in daily life and to inhabit the urban space at the very point where the personal intersects with the public. A present-day representation of remembrance, this procession of “wearable paintings” acts upon our relationship to the world by exploring various forms of urban wanderings while, collectively, making it possible to celebrate our emotional attachment to our loved ones. This secular rite prompts all of us to contemplate the presence of absence—the absence of friends reduced to no more than a scrap of cloth, which kindles a metaphor about the virtues and power of friendship.

Karl-Gilbert Murray, Historien de l'art

1. Forsyth’s work echoes André Breton’s performance during the Dada Festival at the Théâtre de l’Œuvre (Paris, 1920) when he wore a sandwich board with a poster by Francis Picabia upon which was written, “To love something you must have long seen and listened to a passel of idiots.” Calling into question the notion of originality, this performance hoped to shake the received idea of institutionalized art while inviting us to seek elsewhere, in the most unlikely places, for artistic creativity. Sandwich Boards (For My Dearest Friends) also questions the meaning of art much as Daniel Buren, during a site-specific work entitled Hommes-Sandwichs (1968), made it possible to understand the work in another way, through a random meeting, a detour down an alley.

--

L’œuvre Sandwich Boards (For My Dearest Friends) est destinée à déplacer le regard que l’on porte sur l’inertie des choses dans une tentative ultime de rapprochement avec le spectateur. L’activité principale consistant à circuler dans les rues de Toronto, les marcheurs/porteurs, sandwichés entre deux panonceaux, colportent, au-delà des frontières institutionnelles de l’art, une gamme de reproductions peintes de textiles à motifs décoratifs – imitant fidèlement des vêtements ayant appartenu à de proches amis(es) de l’artiste. Conceptuellement1, divulguant nombre de filiations affectives qui transcendent la symbolique iconographique des imprimés géométriques, carrelés et/ou fleuris, chaque placard désigne un(e) ami(e) – absent(e) de corps, mais toujours présent(e) au travers des modalités formelles et stylistiques des étoffes peintes.

Se métamorphosant continuellement au fil des déplacements, l’œuvre révèle ainsi une panoplie d’atavismes culturels qui, selon le contexte et l’influence de l’environnement, provoquent des réminiscences personnelles au travers de rencontres hasardeuses. Portative, elle nous rappelle non seulement l’importance que jouent les vêtements dans l’expérience quotidienne du sens de l’autre, mais aussi que le tissu est une enveloppe corporelle (une seconde peau) qui dit autrement les choses. Nomade, elle défile au gré des aléas des parcours initiés par les marcheurs/porteurs qui, dans leurs interactions aléatoires, mettent en scène des corps-tableaux soutenus par un dispositif de présentation, instaurant une dynamique communicationnelle qui va bien au-delà de la simple déambulation urbaine.

Dès lors, pourrait-on dire que l’œuvre délimite un ensemble de signes distinctifs puisque ces corps-tableaux, qui interpellent des références à l’entourage personnel de Forsyth, tissent une galerie de portraits dont les imprimés, focalisant sur l’aspect ornemental, influencent le jugement (trop souvent façonné par des préjugés). Aussi, dirait-on qu’ayant un fort pouvoir d’évocation, ils convoquent indubitablement autant de souvenirs qui s’éveillent à leurs contacts qu’ils renferment des affects susceptibles de faire surgir des moments oubliés, des paroles, des gestes voire même des odeurs de vie. À cet effet, misant sur le potentiel commémoratif – comme s’il s’agissait d’une adéquation ou d’une analogie stylistique établissant une parenté visuelle entre les tableaux et les individus auxquels ils font référence –, l’œuvre conditionne l’image que l’on se fait de l’autre. Une image inventée au gré de sa subjectivité et de sa créativité dont les procédés de fabrication, intégrant des imprécisions, renforcissent le caractère unique de chaque tableau. L’œuvre discourt ainsi sur la singularité des motifs décoratifs qui, associés au monde des réminiscences émotionnelles, introduisent un sentiment de proximité entre le public et l’œuvre.

Au nom de la démocratisation de l’art, l’œuvre a donc pour volonté de s’inscrire dans la vie quotidienne et d’investir l’espace urbain – là où la vie intime entre en contact avec la vie publique. Représentation contemporaine d’une commémoration, ce défilé de « tableaux portatifs » agit sur notre rapport au monde en explorant diverses figures de la déambulation urbaine tout comme, il permet, collectivement, de célébrer notre attachement affectif avec nos proches. Telle une procession profane, il invite tout un chacun à contempler la présente absence d’amis(es) qui, ne pouvant prendre une autre forme qu’un « lambeau de tissu », induit une métaphore aux vertus et la potestas de l’amitié.

Karl-Gilbert Murray, Historien de l'art

1. L’œuvre de Forsyth, nous rappelle la performance d’André Breton qui, vêtu tel un homme-sandwich, lors du Festival Dada au théâtre de l’Œuvre (Paris, 1920), portait une affiche de Francis Picabia sur laquelle on pouvait lire : « Pour que vous aimiez quelque chose il faut que vous l’ayez vue et entendue depuis longtemps tas d’idiots ». Questionnant la notion d’originalité, cette performance visait à décentrer l’attention que l’on portait sur l’institutionnalisation de l’art tout comme elle invitait à chercher ailleurs la créativité artistique – là où on s’y attendait le moins. Aussi, Sandwich Boards (For My Dearest Friends), interrogeant le sens de l’art tel que Daniel Buren l’aura fait lors d’une intervention in situ, intitulée Hommes-Sandwichs (1968), permet d’appréhender l’œuvre autrement : au hasard d’une rencontre, au détour d’une ruelle, etc.

ASSEMBLY/ABSTRACTION: MICHELLE FORSYTH'S KEVIN'S SHIRTS

Kendra Ainsworth

F'd Up

The Mississauga Art Gallery

Posted March 2014

[ link. ]

[ + Read ]

Amidst the many large, arresting installation pieces in the Art Gallery of Mississauga’s recent exhibition F’d Up!, Michelle Forsyth’s works might seem dwarfed or unobtrusive. But the significance of her art in the context of this exhibition goes far beyond the relative small scale of the works themselves. Taken from a larger series recently exhibited at Auxiliary Projects in Brooklyn, Forsyth’s Kevin’s Shirts makes poignant, if potentially conflicting statements on both our global and personal realities; the work offers a commentary on how as a society we are increasingly out of touch with our physical surroundings, and yet speaks to how we interact, on a very intimate level, with the people and objects we encounter in our day to day lives. Much of the academic and theoretical content of F’d Up! turned an eye on the nature and history of fibre-based art and the connotations associated with the medium. Not only must artists and critics alike contend with the tendency toward categorical distinction between art and “craft,” with fibre-based practice being consigned to the latter group, but more specifically, they must also grapple with the commonly held, if simplistic and potentially apocryphal association of work with fibre and textiles as historically “women’s” work. Here, Forsyth’s work creates an interesting starting point for discussion.

Kevin’s Shirts consists of four 10” by 10” paintings which render the plaid patterns of Forsyth’s husband’s shirts in gouache on paper. The paintings are accompanied by several weavings, haphazardly strewn on the gallery floor, which once again transpose Kevin’s Shirts from their almost abstracted form in painting, back into textile. A cursory reading of the textile components of Forsyth’s work may lead the viewer to thoughts of female labour, either through the historical context of hand or industrial weaving; or more contemporary associations with the traditionally female domestic labour of laundry - the weavings call to mind a disorderly bedroom floor - but the artist counters this notion. In conversation with the author, Forsyth intimated that her husband was always the one to do the laundry in their household. And not only has she never viewed weaving or textile work as “women’s work,” here the textiles serve as an emblem of both how arbitrary these gendered associations are – heaps of cloth on the ground speak to the absence of Kevin and his domestic efforts – and of the intrinsically personal quality that objects take on in our lives. For Forsyth, the fibre elements in her work are more about intimacy than gender.

Starting this particular series while her husband was away on sabbatical, Forsyth was looking to document, capture and remember her husband through the tangible traces he left in their living space – his clothing, a uniform of plaid shirts. She began painting, taking the mass-produced textile patterns and at once bringing them into the abstract, and at the same time reconnecting them with the artist’s or maker’s hand.

Glenn Adamson asserts in The Invention of Craft that craft is something that was created alongside industry as its other, rather than something industry arose out of or advanced from. Forsyth produces a form of “craft” that not only acts as a foil for industrial production but that “others” it. Mass-produced clothing goes through so many processes, places and machines in its travels from the designer’s sketchbook to our closets, and yet it is so ubiquitous and normal that we frequently don’t consider the global industries and implications of its production. Through her paintings, Forsyth takes these products, rich in material history and political and economic significance, back to their most basic component parts: colour, line, and pattern, rendering the original reference preternatural in the process.

In creating a simulacrum of these shirts, which themselves epitomize our age of industrial facsimile, Forsyth calls attention to how removed we are from the production of items we use every day. Our disassociation, or abstraction from the Real is effectively countered through painterly abstraction. Although Forsyth’s paintings are inherently representative, this second order abstraction - as it serves to dissociate and decontextualize the component elements of Kevin’s Shirts , and by extension all manufactured products, from their original ground - forces us to slow down and contemplate the process of this new form of creation. This forced change of perspective is also compounded by the stylistic elements of the paintings, which call to mind the meditative quality of Agnes Martin and similar artists associated with abstract expressionism. And ironically, it is this abstraction that actually reintroduces the idea of the maker or creator back into the process of production. Upon close inspection, the artist’s hand is visible in the subtle irregularities of paint and composition – making visible the labour of creation; a physical inscription of the methods of production into the picture. This maker is brought even more evidently to the forefront as the paintings are transcribed from the page to the loom, and back to the very roots of textile work, to the traditionally “hand-made.”

Interestingly, Forsyth, a painter, only learned to weave for this project, feeling that the paintings just needed to become textiles. Where she enjoys the doubling and tripling of the same pattern, each version with its attendant variations, this transposition of the simulacra back (or forward) into fibre re-contextualizes the original subject. And even as Kevin’s Shirts move through these artistic iterations and are abstracted further and further from both the intent and implications of their initial form, to Forsyth, all forms are her husband’s shirts. In this sense, all the components of Kevin’s Shirts are a paean to the intimate connections that we have with everyday objects. Forsyth notes that artists are well placed to call our attention to these connections and relationships; painters often work alone in the studio, seeing and using the same objects every day, imbuing them with almost a magical, ritualistic significance. Indeed it is these objects that she saw every day that served as inspiration for Forsyth – objects that, although ordinary and mass produced, were already inherently ripe with significance in their status as markers of absence. If we view craft as a process, a way of doing things, and something that is inherently tied to material experience, perhaps it is fitting that Kevin’s Shirts is entirely dependent on process – the transformation of artifact to painting and then to textile sculpture. Here, Forsyth’s artistic practice in and of itself serves to reinvigorate our notions of what craft is. Not a lesser cousin to “art” nor an essentially gendered practice, it is a way of thinking through the world, and our personal connections to our surroundings. And that is something that we can all appreciate.

- Kendra Ainsworth

Assistant Curator at the Art Gallery of Mississauga, is an interpretive planner and curator. She has a Masters in Museum Studies and a B.A in Cultural Anthropology from the University of Toronto, and has been working in the arts and culture sector for over six years. She is strongly committed to making museums and galleries of contemporary art and craft intellectually, physically and emotionally accessible spaces for visitors. Through creative curation and interpretation, Kendra aims to remove both intangible and tangible barriers to public engagement with contemporary art, and allow it to serve as a catalyst for community building and intellectual development for people of all ages. Past projects have included exhibitions at the Burlington Art Centre (The Art of the Cut: Papercuttings by Lini Grol, 2013), the Gardiner Museum (Sugar and Spice, 2011) and the Art Gallery of Ontario (At Work: Hesse, Goodwin, Martin, 2010).

WARP & WEFT

Sharon Butler

Two Coats of Paint (Blog)

February 4, 2013

[ link. ]

[ + Read ]

A faculty member at the state university in Pullman, Washington, Michelle Forsyth is undoubtedly surrounded by plaid. Once the symbol of the Scottish Highlands, in the 1990s plaids shirts came to symbolize the Northwest grunge aesthetic and have since become a staple of mainstream fashion vernacular. In "Letters for Kevin," a solo show at Auxiliary Projects, Forsyth presents a series of paintings and hand-woven cloths that reference the plaid patterns of her husband Kevin’s shirts.

Tacked on the wall in a grid formation, 94 small studies transcribe the mass-produced plaids into a heart-felt, painterly language, replete with crooked lines, pooled paint and rough edges. Both observational and abstract, Forsyth's paintings conjure Sylvia Plimack-Mangold’s 1970s wooden floor paintings and Lula Mae Blocton’s less familiar depictions of Kente cloth.

The charming installation at tiny Auxiliary Projects also includes several woven plaid cloths that Forsyth made on a loom, a small mural, and an elegant painting on linen. Perhaps referencing laundry and domestic tedium, one cloth is thrown in the corner and the others are stacked in a neatly folded pile. Forsyth’s work seems to suggest that despite our inundation with mass-produced goods and our ready conformance to sartorial stereotypes, singular expression and reverie can flourish, even within the most mundane domestic circumstances.

OVER AND OVER AGAIN, THE NATURE OF MEMORY

Frances De Vuono

Over & Over Catalog

The Hogar Collection, Brooklyn, NY

February 3, 2010

[ Download pdf 40kb. ]

[ + Read ]

There is something at once both lush and sharp about what Michelle Forsyth does as an artist. In nearly everything she makes—from small works on paper to large installations—she affirms the handmade. From a distance her works often lock into representation, a suggestion of narrative and place, but close examination reveals that the images are made of cutout pieces of fabric and paper, beads stitched to the paper or mounted on with dressmaker’s pins. Many of her most recent pieces have additional layers of prints on their surface. For this, Forsyth begins with hand drawing on film; she then exposes these drawings onto the screens and, like traditional fabric artisans across the world, she repetitively pushes the inks through the screens onto the paper over and over again. This is work that celebrates the laborious.

Forsyth is interested in history, specifically public and private memories of tragedies and traumas. To this end, she makes her images by embarking on a series of activities. For each of the pieces in both the 100 Drawings and Ostinatos series here, she begins by researching an event through archived media; then she travels to the site where the incident originally took place and photographs the spot. Neither the tragedy itself, these well-sequenced steps, nor her conceptually loaded purpose stops Forsyth from additionally reveling in beauty. In all her work (excepting the Text Works) she manipulates our penchant for pleasure, loading her carefully crafted documentations with vibrant colors as if they were tapestries.

In his novel, Love in the Time of Cholera, Columbian author Gabriel García Márquez referred to memory’s pathway towards nostalgia as a disease. Forsyth, born in Canada, at a colder, near opposite end of the American hemisphere, must have a similar feeling about memory and its ability to course through time, mutating and changing along the way. Forsyth consciously photographs a chosen disaster such as Tacoma Narrows Bridge Collapse, Tacoma, WA, November 7, 1940 years after it actually took place. The artist’s deliberate acknowledgement of years passed implies that something can still be gained by remembering and seeing, as though the geography holds unseen particles of its past. In the studio, Forsyth then isolates elements from these photographic records and breaks them down further into minute units, which she finally, painstakingly reconstructs back into images again. The results are a plethora of shapes and colors with their own abstract logic that initially makes no narrative sense until we move back. Standing close to a work like Hoboken Pier Fire, Hoboken, NJ, June 30, 1900 is akin to having used the zoom function on a digital camera or a computer. It is a pixilated image, rendered into 3-D by its compounded materials, but we only see it as a real place when we move away from it. And that, of course, is arguably the best way to make sense of our past as well. Forsyth’s description of historical events fractured into tiny bits, suggests that memory could be—or should be—a kind of hologram, only truly understood within the context of its many parts.

While it is clear that Forsyth’s pieces pay tribute to the handmade, it would be a disservice not to acknowledge her equally crucial engagement with technology. Describing the early stages of her process in doing research and in organizing her images, Forsyth states that she takes images “culled from television, newspapers, and the Internet…” using a grid, she translates this visual information into the vibrantly tactile work seen here, variously using cotton thread, bits of gouache painted papers, crystal and more. Conscious of the implications between her ideas and working methods, she explains, “The grid becomes a nexus between the bitmapped images [of the computer] and the hand-crafted ones.” Her very language confirms the importance contemporary technologies play in her work, affirming the observations made by artist (and now theorist) David Hockney who claimed in his book Secret Knowledge, that artists have always embraced the technology of their times and that the best ones turn it to the service of their ideas. Forsyth admits that freely. But in her case, she adds “I use technology to slow my process down instead of speed it up.”

This exhibition draws from three different series done over the past four years: 100 Drawings, Ostinatos and Text Work. While both the two former series use the processes described above and are layered with colors, forms and materials, Text Work does something unexpected but utterly in keeping with Forsyth’s purpose. Using the same newspapers and online sources where Forsyth habitually gathers her visual imagery, for Text Work she eschews color and collected material. Instead she extracts the actual words that witnesses have used to describe historical events. She isolates their verbal responses the way she had formally isolated patterns from pictures, taking phrases and carefully punching them into paper. The resulting pieces are made of light and absence. The shapes that the cutout type leaves are a pentimento of text. It is a ghost of meaning and memory. Showing this simpler, quieter series in conjunction with the more layered works makes for a perfect pairing. Edwin (eyewitness) and Tacoma Narrows Bridge Collapse, Tacoma, WA, November 7, 1940 demonstrate this explicitly because they both deal with the aftermath of the same disaster. But all three series work in a kind of rewarding synchronicity.

Seeing the richly layered Ostinatos and 100 Drawings in conjunction with the spare, punched out ‘imagery’ of Text Works is a deft curatorial move. What the two different visual depictions suggest is that while we tend to understand our past by aggregate information, we also need to remember that absence of data, information and material is an equally integral part of its nature. We need both.

MICHELLE FORSYTH: AN INTRODUCTION

Brian Grison

Canopy Brochure

USM Art Gallery, Gorham, ME

February 24, 2009

[ Download pdf 324kb. ]

[ + Read ]

Writing is a form of therapy; sometimes I wonder how all those who do not write, compose or paint can manage to escape the madness, the melancholia, the panic fear that is inherent in the human condition.

—Graham Greene

The origin of an artist’s work is often found in childhood experience rather than in education or influences. It is useful to know how these origins continue to resonate through an artist’s later life and work. Writing in Solitude: A Return to the Self, psychologist Anthony Storr outlines how many artists’ creativity, often in the form of life-long projects, develop as compensation for childhood trauma. This essay about Michelle Forsyth’s art and practice will reflect Storr’s observation.

Michelle Forsyth grew up on sailboats; between ages eight and sixteen she sailed with her family for three months each summer through Desolation Sound off the coast of British Columbia. Unfortunately, for the young Michelle, sailing seemed acutely dangerous and disaster-prone. Every day she expected the worst. Her constant anxiety and watchfulness evolved into daydreamed stories about disasters at sea, forest fires, urban destruction and the end of the world. Novels about shipwrecks and other disasters that her father enjoyed reading further encouraged her imaginary fears. Children like to frighten themselves, but in this case, there appears to have been no escape, and Michelle hated being frightened.

However, the ocean can be frightening. A sailor must always be careful, and always be prepared for, if not actually expecting, the worst. A sailboat is designed for the dynamic environment of waves, tides, currents and wind. Sailing life is often reduced to holding on, watching the approaching waves or shore, and shouting warnings and instructions. Probably the young Michelle and her two sisters always wore lifejackets, a metaphoric safety line to the boat, but no guarantee of security. She remembers having to watch for rocks while her father maneuvered the boat in tight places. It did not help that he was an aggressive sailor who enjoyed sailing flat out against the wind, and liked putting his family on edge with daredevil antics.

Today, memories of the insecurity of her sailing childhood have evolved into a psychologically and culturally difficult subject and methodology in her art practice. She now searches for a stable balance among her memories, anxieties and craft-like systems in her studio practice to depict the real historic disasters that her work commemorates. Through a kind of voyeurism, she compulsively unravels the personal psychological impact of the dangerous world, both real and imagined, that she was brought up in, as well as actual historic and contemporary disasters she witnesses through television and the media. These concerns supersede aesthetic, craft process and social or political concerns.

Much of Michelle Forsyth’s art prior to this exhibition can be characterized as documentations of secret ritualistic pilgrimages to scenes of disasters, which she experiences obliquely and intuitively. Instead of employing historic photographs, she surreptitiously records metaphors of the site through digital images of mundane near-by presences, such as flowers or clouds, which have no relationship with the historic disaster. The photographs are then translated into thousands of tiny brightly colored, mosaic-like, brush marks, cut paper shapes, found material and glitter, which she paints, or stitches to paper, or pins to walls. She does not recreate images of the disaster itself. Instead, her paintings, empty of horror, are an elegy to the social loss of memory of these events.

Two works related to the same disaster encompass the full range of Forsyth’s concerns and methods. On June 17, 1958, the Second Narrows Bridge in Vancouver collapsed during construction. Eighteen workers were killed. Michelle Forsyth’s grandfather, who was fishing for crab nearby, was able to rescue several men who had fallen into the water. In the 1990’s the bridge was renamed the Ironworker’s Memorial Second Narrows Crossing, with memorial plaques at both ends.

In the small watercolor and gouache drawing from 2007, Second Narrows Bridge Collapse, Vancouver BC, June 17, 1958, Michelle Forsyth depicts a few small wild flowers near the north end of the bridge. Only vague shapes and color emerge through elaborate patterning to reference the flowers, though they coalesce slightly through squinting. There is no clear pointer to the bridge collapse. Instead, the viewer is drawn into the mesmeric interplay of the carefully applied layers of pattern and color. The historic disaster, as well as its memory, has faded away.

The second, much larger, work is more ambitious. June 17, 1958 (for my grandfather), produced a few months later in 2007, is materially closer to Forsyth’s creative origins in knitting and needlework, which her mother taught her. Based on a slightly different digital photograph of the same group of flowers, the image has been divided into one-foot sections and then gridded. Forsyth organized a replica of this pattern with one-inch thick pieces of Styrofoam. Into the center of each one-inch grid across the Styrofoam she pins several layers of flower-like shapes that she spends hours cutting from painted paper, Color-aid paper, sandpaper, decorative papers, beads, sequins and glitter. These assorted colors and textures that accumulate on each pin replicate the colors of the photograph in much the way that French Impressionist paintings reduced the subject to a loose grid of colored spots. Once complete the pins were transferred from the Styrofoam to the gallery wall.

This memorial to Michelle Forsyth’s grandfather’s heroic action during the collapse of the Second Narrows Bridge is closer in materials and methods, as well as spirit, to the installation, titled Canopy, she has constructed at the University of Southern Maine. The knowledge and assurance that her grandfather could set the precarious world right for others, and therefore for herself, must be read as a milestone in her career. Chronic grief as negative self-identity has shifted to the notion that the hard work, both physical and psychological, that she learned her craft methods is a meditation on the lifeline between a traumatic childhood and her mature self, and points to the new theme of the canopy as a source or protection in her newest project.

— Brian Grison

Brian Grison is an artist and writer currently living in Victoria BC Canada. He holds a BFA and a BA from the University of Victoria, and an MA from Carleton University, Ottawa.

MICHELLE FORSYTH: INTERVIEW

David Drake

Field Work Catalog

Zaum Projects Contemporary Art, Lisbon, PT

October 30, 2008

[ Download pdf 48kb. ]

[ + Read ]

The following conversation took place between the Michelle Forsyth and David Drake via email during the Month of October 2008.

DD. We've talked about connections between your work and the ideas and strategies of the first generation of conceptual artists. Some of those connections I think are quite clear: the "Drawings" continue investigations into the philosophical problem of presence and absence, for example. But other strategies you employ I'm tempted to regard as radically different, particularly the way you approach art-as-object. Your objects are not dematerialized, demystified and stripped of their aura; rather, through craft, you've raised up humble materials (sandpaper, felt), and applied a jewel-like aura to them. You've attempted to re-invest banality with meaning, maybe even mystery.

And, I want to say, these objects you make--these traces of obsessive studio practice, of travel to the sites of used-up disasters--these objects are also unapologetic commodities. They sell.

I say I'm tempted to regard all this as differing radically with conceptual antecedents. In fact, I think this is also an area of connection: that a similar set of interests results in a drive to dematerialize and decomodify at one time, and the opposite at another.

MF. I am really glad you have brought this up. It is something that I do struggle with. On the one hand I am ultimately driven by moving my work along a solid conceptual trajectory yet on the other I get fully caught up in the materials I chose to work with. I guess I was first interested in the spectacular images that these events conjured up in my mind--exploding ships, bridge collapses, burning forests--and that sense of drama is something that can be seen in the way my materials catch the eye, but what I am ultimately thinking about is how I can pay homage to what is left behind. When I traveled to the first few sites I found myself a little disappointed by what I found there. There wasn’t much to see--a few dandelions or some scrap tires--but when I brought my images back to the studio and set to work I just started trying to fill the absence with the accumulation of residue left behind by my working processes.